When we think of a “midcentury modern” home, we think of glass walls. In part, this has to do with the post-World War II decades’ promotion of the southern California-style indoor-outdoor suburban lifestyle. But business and culture are downstream of technology, and, in this specific case, the technology known as insulated glass. Its development solved the problem of glass windows that had dogged architecture since at least the second century: they let in light, but even more so cold and heat. Only in the 1930s did a refrigeration engineer figure out how to make windows with not one but two panes of glass and an insulating layer of air between them. Its trade name: Thermopane.

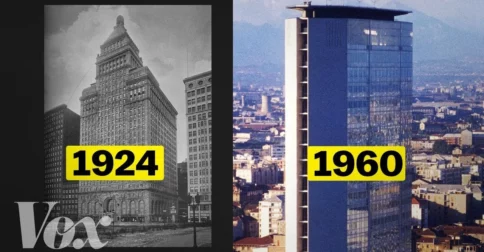

First manufactured by the Libbey-Owens-Ford glass company, “Thermopane changed the possibilities for architects,” says Vox’s Phil Edwards in the video above, “How Insulated Glass Changed Architecture.” In it he speaks with architectural historian Thomas Leslie, who says that “by the 1960s, if you’re putting a big window into any residential or office building” in all but the most temperate climates, you were using insulated glass “almost by default.”

Competing glass manufacturers introduced a host of variations on and innovations in not just the technology but the marketing as well: “No home is truly modern without TWINDOW,” declared one brand’s magazine advertisement.

The associated imagery, says Leslie, was “always a sliding glass door looking out onto a very verdant landscape,” which promised “a way of connecting your inside world and your outside world” (as well as “being able to see all of your stuff”). But the new possibility of “walls of glass” made for an even more visible change in commercial architecture, being the sine qua non of the smoothly reflective skyscrapers that rise from every American downtown. Today, of course, we can see 80, 900, 100 floors of sheer glass stacked up in cities all over the world, shimmering declarations of membership among the developed nations. Those sliding glass doors, by the same token, once announced an American family’s arrival into the prosperous middle class — and now, more than half a century later, still look like the height of modernity.

Related content:

Why Do People Hate Modern Architecture?: A Video Essay

How the Radical Buildings of the Bauhaus Revolutionized Architecture: A Short Introduction

Why Europe Has So Few Skyscrapers

A Glass Floor in a Dublin Grocery Store Lets Shoppers Look Down & Explore Medieval Ruins

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

0 Commentaires