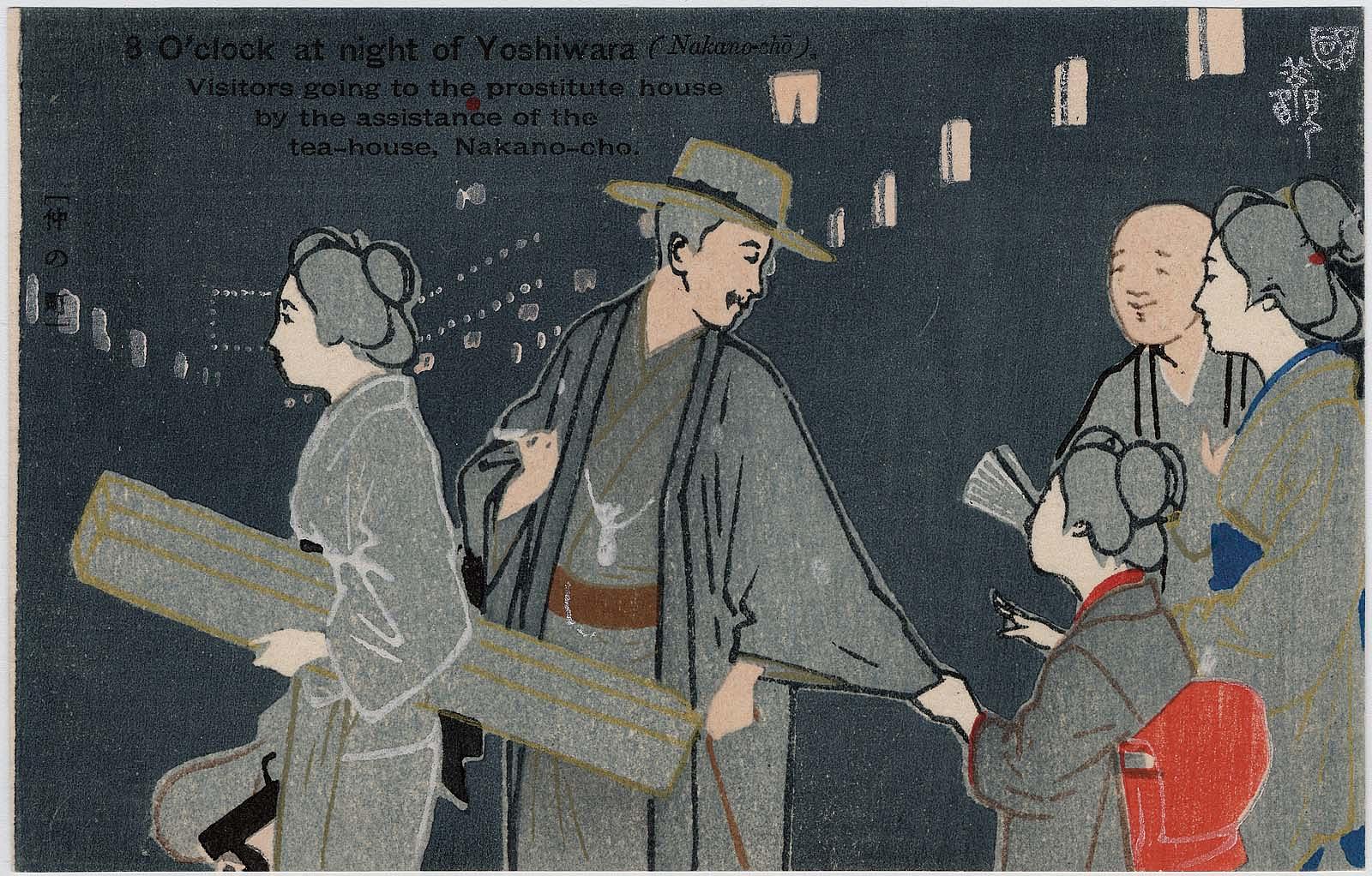

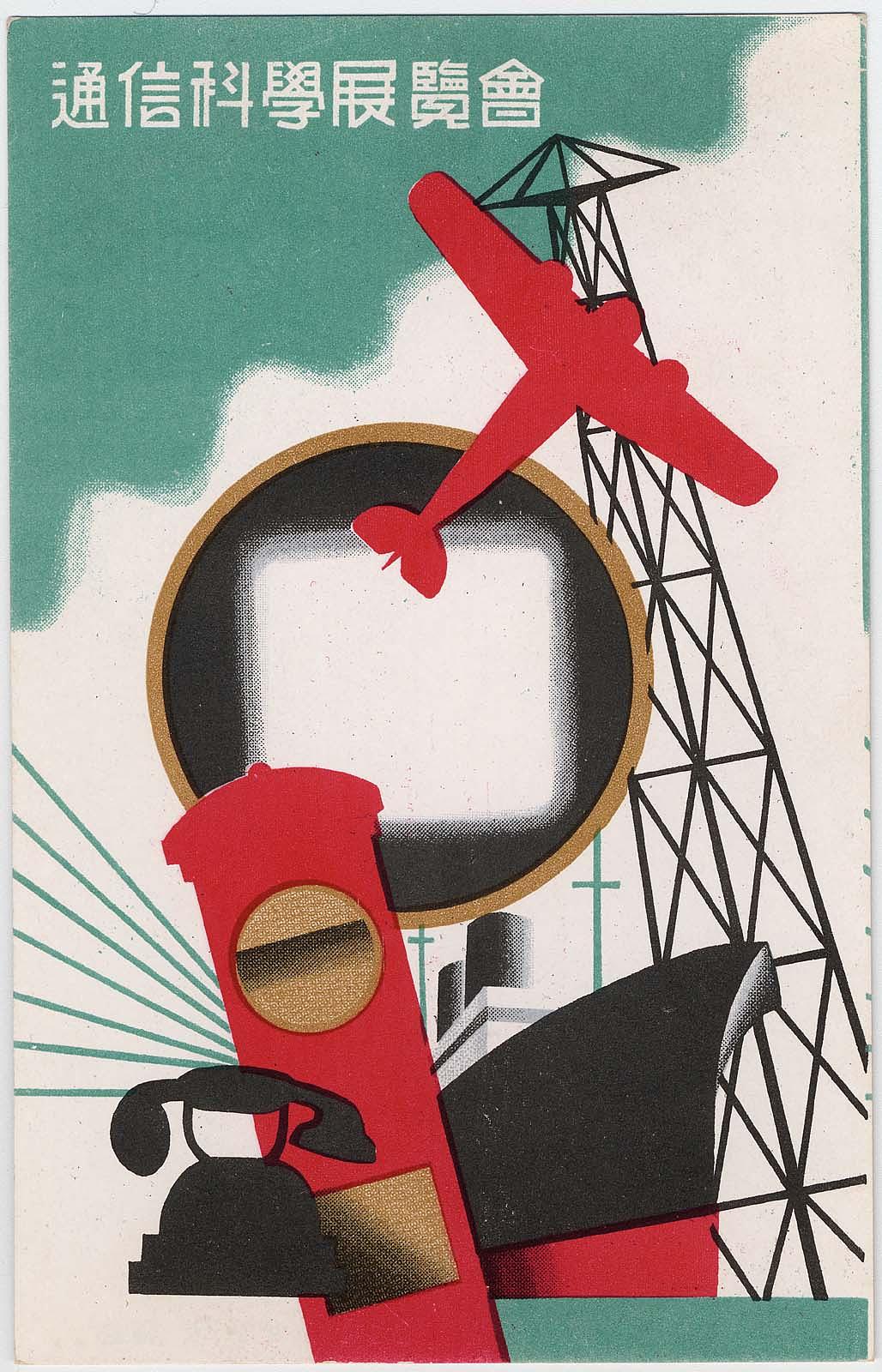

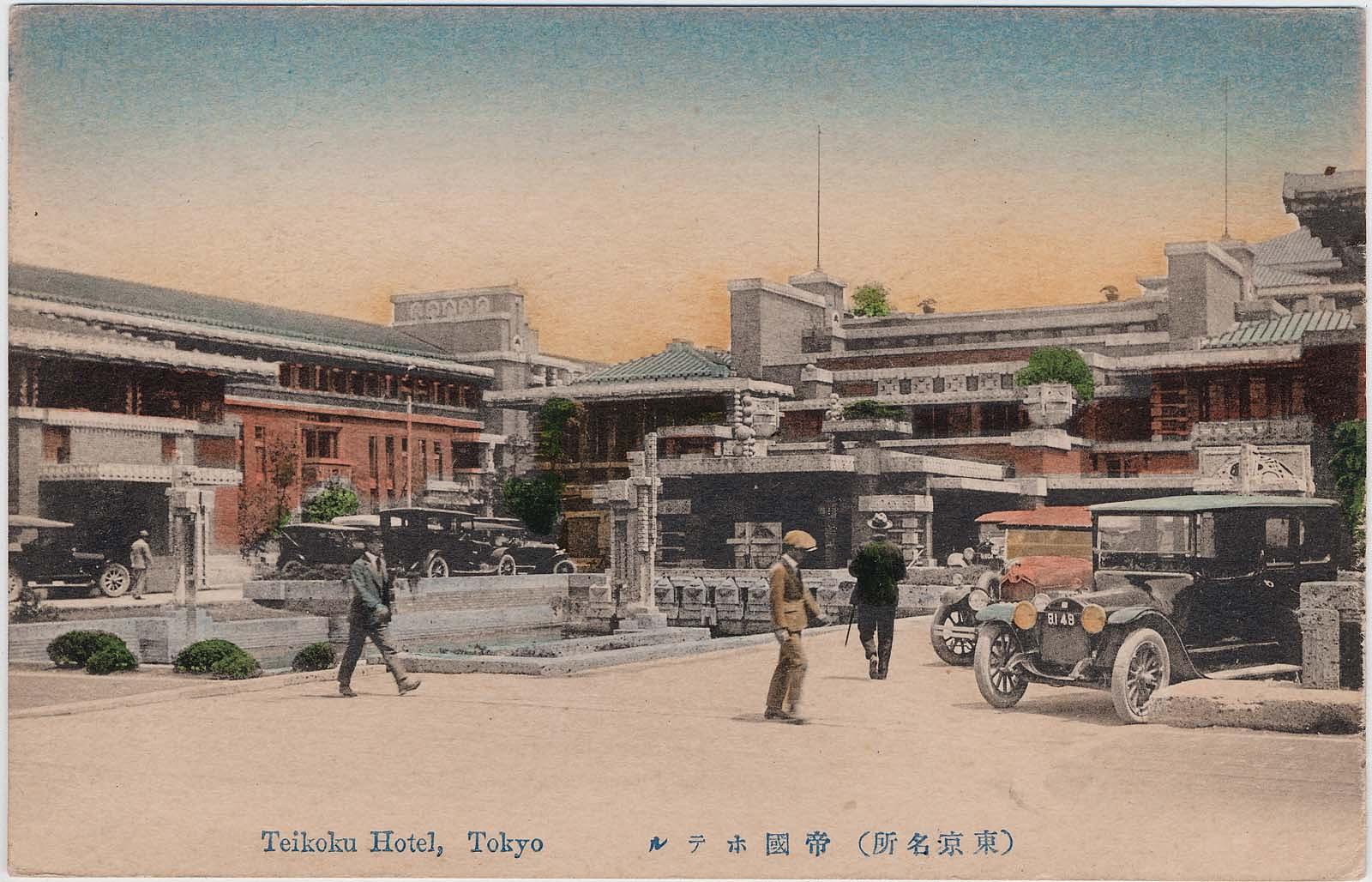

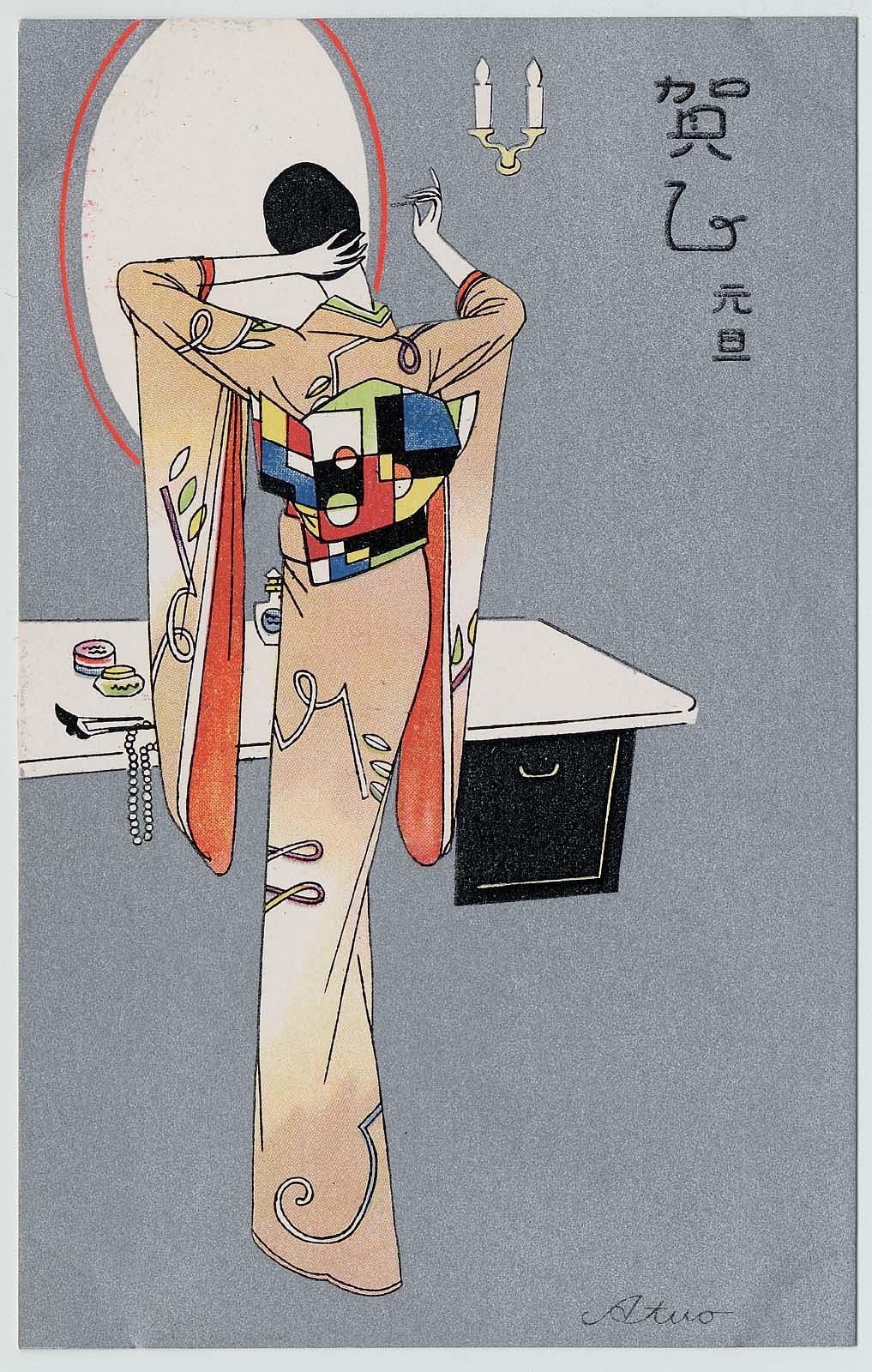

The world thinks of Japan as having transformed itself utterly after its defeat in the Second World War. And indeed it did, into what by the nineteen-eighties looked like a gleaming, technology-saturated condition of ultra-modernity. But the standard version of modernity, as conceived of in the early 20th century with its trains, telephones, and electricity, came to Japan long before the war did. “Between 1900 and 1940, Japan was transformed into an international, industrial, and urban society,” writes Museum of Fine Arts Boston curator Anne Nishimura Morse. “Postcards — both a fresh form of visual expression and an important means of advertising — reveal much about the dramatically changing values of Japanese society at the time.”

These words come from the introductory text to the MFA’s 2004 exhibition “Art of the Japanese Postcard,” curated from an archive you can visit online today. (The MFA has also published it in book form.) You can browse the vintage Japanese postcards in the MFA’s digital collections in themed sections like architecture, women, advertising, New Year’s, Art Deco, and Art Nouveau.

These represent only a tiny fraction of the postcards produced in Japan in the first decades of the twentieth century, when that new medium “quickly replaced the traditional woodblock print as the favored tableau for contemporary Japanese images. Hundreds of millions of postcards were produced to meet the demands of a public eager to acquire pictures of their rapidly modernizing nation.”

The earliest Japanese postcards “were distributed by the government in connection with the Russo-Japanese War (1904–5), to promote the war effort. Almost immediately, however, many of Japan’s leading artists — attracted by the informality and intimacy of the postcard medium — began to create stunning designs.” The work of these artists is collected in a dedicated section of the online archive, where you’ll find postcards by the commercial graphic-design pioneer Suguira Hisui; the French-educated, highly Western-influenced Asai Chi; the multitalented Ota Saburo, known as the illustrator of Kawabata Yasunari’s The Scarlet Gang of Asakusa; and Nakazawa Hiromitsu, creator of the “diver girl” long well-known among Japanese-art collectors.

Surprisingly, Nakazawa’s diver girl (also known as the “mermaid,” but most correctly as “Heroine Matsuzake” of a popular play at the time) seems not to have been among the possessions of cosmetics billionaire and art collector Leonard A. Lauder, who donated more than 20,000 Japanese selections from his vast postcard collection to the MFA. “In 1938 or ’39, a boy of five or six, or maybe seven, was so enthralled by the beauty of a postcard of the Empire State Building that he took his entire five-cent allowance and bought five of them,” writes the New Yorker‘s Judith H. Dobrzynski. The youngster thrilling to the paper image of a skyscraper was, of course, Lauder — who couldn’t have known how much, in that moment, he had in common with the equally modernity-intoxicated people on the other side of the world.

via Flashbak

Related content:

Advertisements from Japan’s Golden Age of Art Deco

Vintage 1930s Japanese Posters Artistically Market the Wonders of Travel

Glorious Early 20th-Century Japanese Ads for Beer, Smokes & Sake (1902-1954)

An Eye-Popping Collection of 400+ Japanese Matchbox Covers: From 1920 through the 1940s

View 103 Discovered Drawings by Famed Japanese Woodcut Artist Katsushika Hokusai

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600-1915)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

0 Commentaires