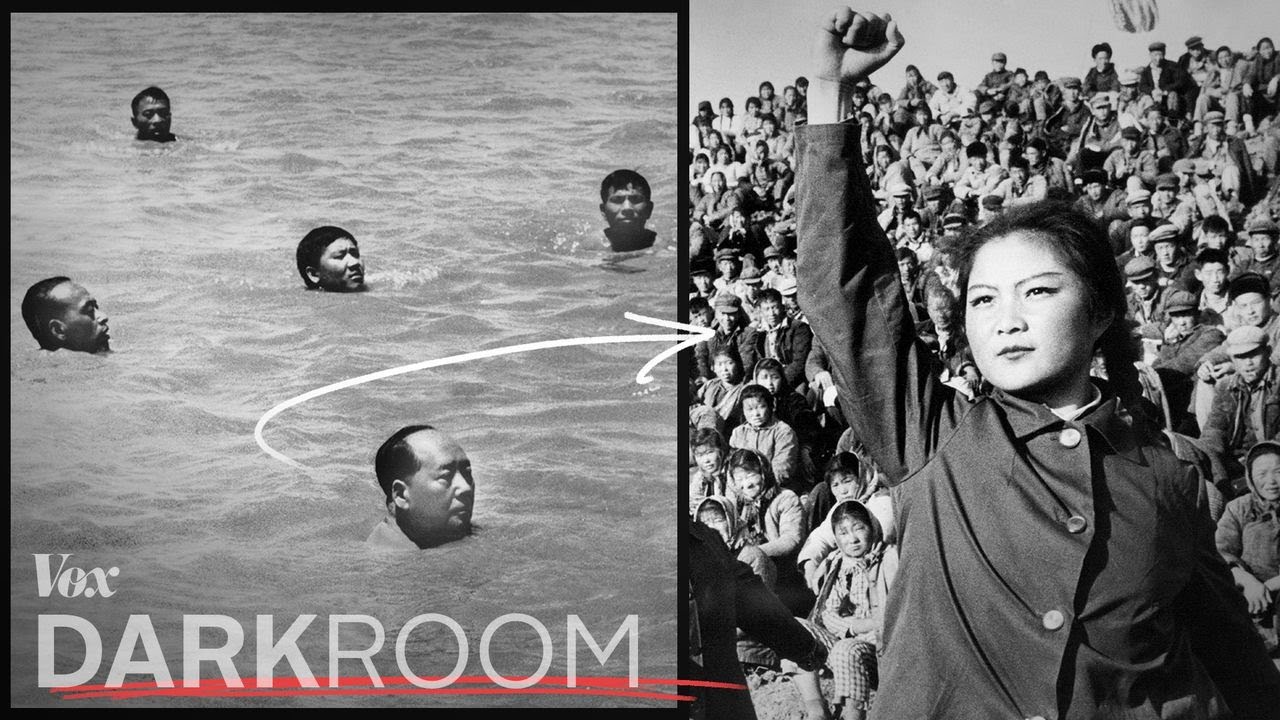

In 1958, Mao Zedong launched the Great Leap Forward. Eight years later, he announced the beginning of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Between those two events, of course, came the Great Chinese Famine, and historians now view all three as being “great” in the same pejorative sense. Though Chairman Mao may not have understood the probable consequences of policies like agricultural collectivization and ideological purification, he did understand the importance of his own image in selling those policies to the Chinese people: hence the famous 1966 photo of him swimming across the Yangtze River.

By that point, “the Chinese leader who had led a peasant army to victory in the Chinese Civil War and established the communist People’s Republic of China in 1949 was getting old.” So says Coleman Lowndes in the Vox Darkroom video above. Worse, Mao’s Great Leap Forward had clearly proven calamitous. The Chairman “needed to find a way to seal his legacy as the face of Chinese communism and a new revolution to lead.” And so he repeated one of his earlier feats, the swim across the Yangtze he’d taken in 1956. Spread far and wide by state media, the shot of Mao in the river taken by his personal photographer illustrated reports that he’d swum fifteen kilometers in a bit over an hour.

This meant “the 72-year-old would have shattered world speed records,” a claim all in a day’s work for propagandists in a dictatorship. But those who saw photograph wouldn’t have forgotten what happened the last time he took such a well-publicized dip in the Yangtze. “Experts feared that Mao was on the verge of kicking off another disastrous period of turmoil in China. They were right.” The already-declared Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, now widely known as the Cultural Revolution, saw millions of Chinese youth — ostensibly radicalized by the image of their beloved leader in the flesh — organize into “the fanatical Red Guards,” a paramilitary force bent on extirpating, by any means necessary, the “four olds”: old culture, old ideology, old customs, and old traditions.

As with most attempts to usher in a Year Zero, Mao’s final revolution wasted little time becoming an engine of chaos. Only his death ended “a decade of destruction that had elevated the leader to god-like levels and resulted in over one million people dead.” The Chinese Communist’s Party has subsequently condemned the Cultural Revolution but not the Chairman himself, and indeed his swim remains an object of yearly commemoration. “Had Mao died in 1956, his achievements would have been immortal,” once said CCP official Chen Yun. “Had he died in 1966, he would still have been a great man but flawed. But he died in 1976. Alas, what can one say?” Perhaps that, had the aging Mao drowned in the Yangtze, Chinese history might have taken a happier turn.

Related content:

Wonderfully Kitschy Propaganda Posters Champion the Chinese Space Program (1962-2003)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

0 Commentaires