Literacy in Chinese may now be widely attained, but it isn’t easily attained. Just a century ago it wasn’t widely attained either, at least not by half of the Chinese speakers alive. As a rule, women once weren’t taught the thousands of logographic characters necessary to read and write in the language. But in one particular section of the land, Jiangyong County in Hunan province, some did master the 600 to 700 characters of a phonetic script made to reflect the local dialect and now called Nüshu (女书), or “women’s writing.”

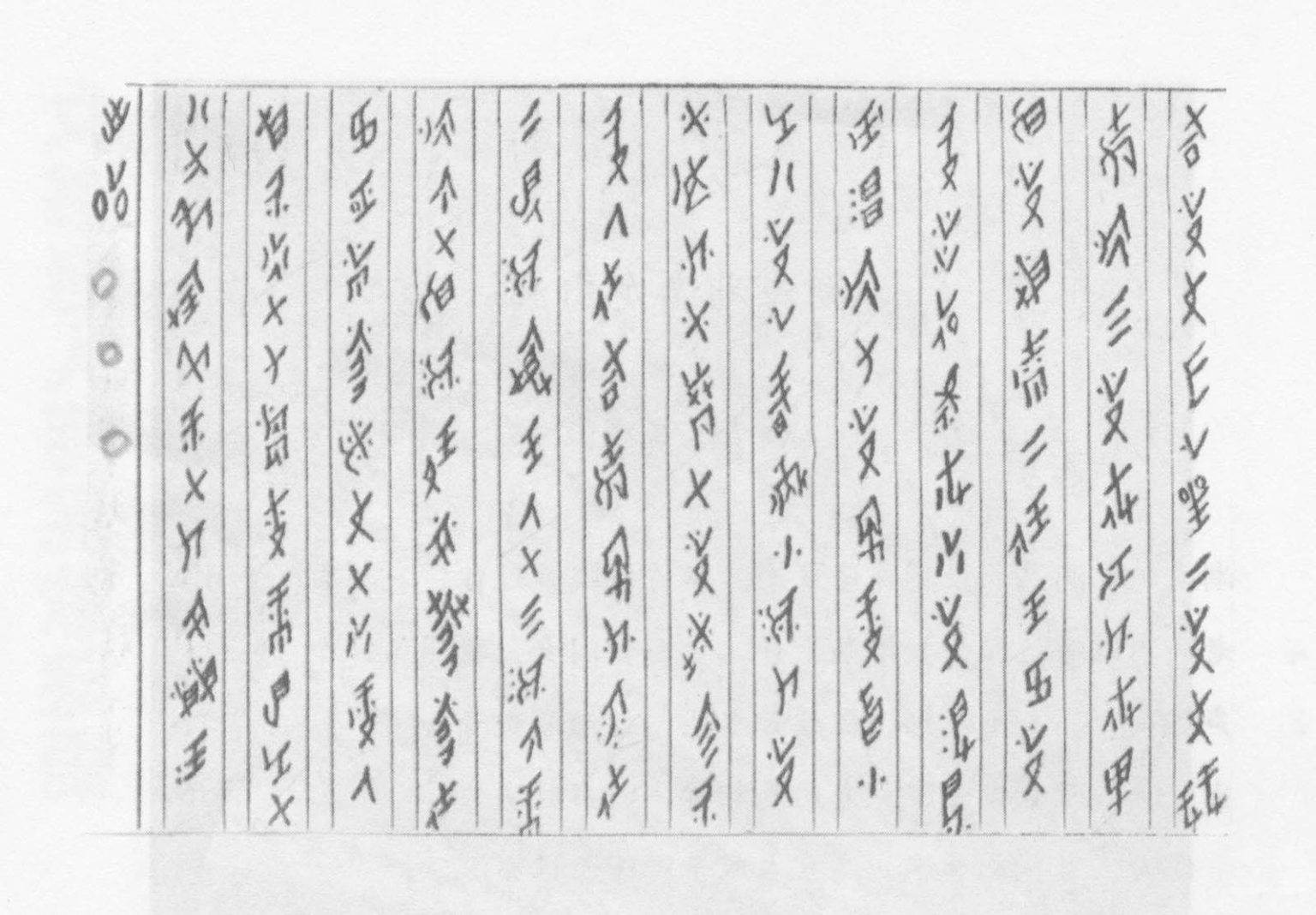

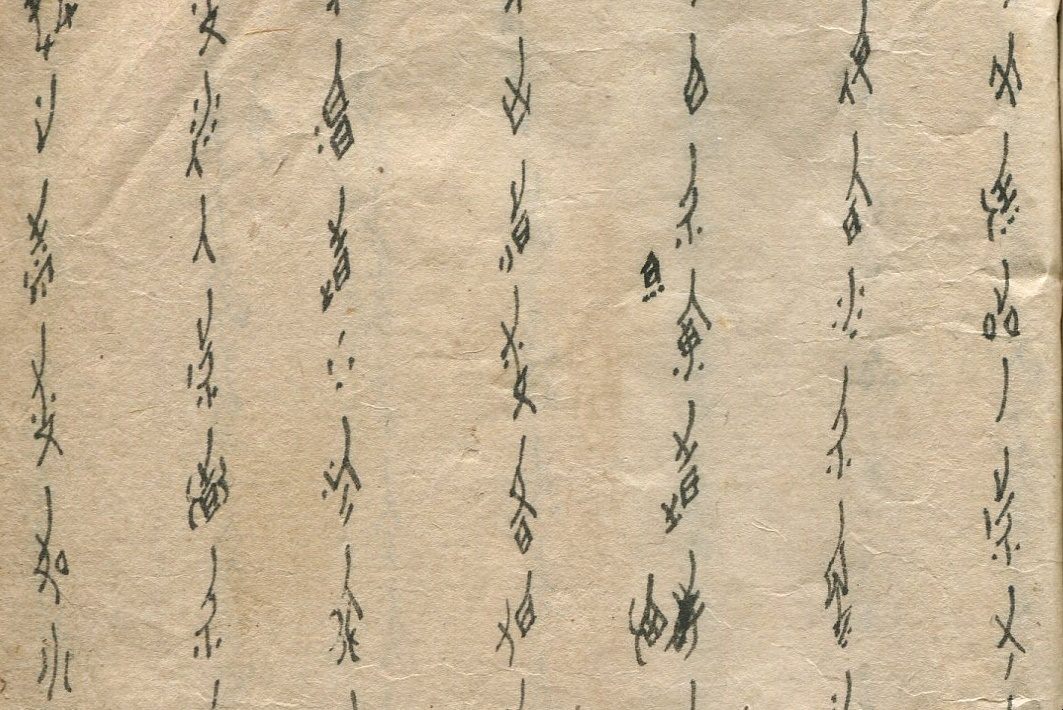

In its heyday, Nüshu’s users had a variety of names for it, “including ‘mosquito writing,’ because it is a little slanted and with long ‘legs,'” writes Ilaria Maria Sala in a Quartz piece on the script’s history. Its greatest concentration of practitioners lived in “the village of Shangjiangxu, where young girls exchanged small tokens of friendly affection, such as fans decorated with calligraphy or handkerchiefs embroidered with a few auspicious words.”

Other, more formal occasions for the use of Nüshu, included when girls decided to “make a full-fledged pact of closeness with one another that they were ‘best friends’ — jiebai zimei or ‘sworn sisters’ — a relationship that was recognized as valuable and even necessary for them in the local social system. Such a once-obscure chapter of Chinese history has proven irresistible to readers from a variety of cultures in recent decades.

“Most interpretations and headlines have been about a ‘secret language’ that women used, preferably to communicate their pain,” writes Sala, which struck her as evidence of people taking the story of Nüshu and “reading into it what they wanted, regardless of what it meant.” Yet such an interpretation has surely done its part to spread interest in the near-extinct’s script’s revival, described by BBC.com’s Andrew Lofthouse as originating in “the tiny village of Puwei, which is surrounded by the Xiao river and only accessible via a small suspension bridge.” After three Nüshu writers were discovered there in the eighties, “it became the focal point for Nüshu research. In 2006, the script was listed as a National Intangible Cultural Heritage by the State Council of China, and a year later, a museum was built on Puwei Island.”

There training is provided to the few select “interpreters or ‘inheritors’ of the language, learning to read, write, sing and embroider Nüshu.” Ironically, Lofthouse adds, “much of what we know about Nüshu is due to the work of male researcher Zhou Shuoyi” who happened to hear of it in the nineteen-fifties and was later persecuted during Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution — a treatment that included 21 years in a labor camp — for having researched such an artifact of the feudal past. Once a useful tool for expressing emotions and performing social rituals socialization, Nüshu had become politically dangerous. What it becomes now, half a century later and with its renewal only just beginning, is up to its new learners.

Related content:

How Writing Has Spread Across the World, from 3000 BC to This Year: An Animated Map

How to Write in Cuneiform, the Oldest Writing System in the World: A Short, Charming Introduction

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

0 Commentaires