If a painter is ahead of his time, his work won’t sell particularly well while he’s alive. If an architect is ahead of his time, his work probably won’t exist at all — not in built form, at least. Such was the case with Étienne-Louis Boullée, who constructed few projects in the eighteenth century in which he lived, almost none of which remain standing today. The best Boullée devotees can do for a site of pilgrimage is the Hôtel Alexandre in Paris’ eighth arrondissement, which, though handsome enough, doesn’t quite offer a sense of why he would have devotees in the first place. To understand that, one must look to Boullée’s unbuilt works, the most notable of which are introduced in the video from Kings and Things above.

“Paper architect” identifies a member of the profession who may design structures prolifically but seldom, if ever, builds them. It is not a desirable label, especially in its implication of willful impracticality (even by architectural standards). But as practiced by Boullée, paper architecture became an art form unto itself: he left behind not just an extensive essay on his art, but voluminous drawings that envision a host of neoclassical buildings as ambitious in his time as they were unfashionable — and often, due to their sheer size, unbuildable.

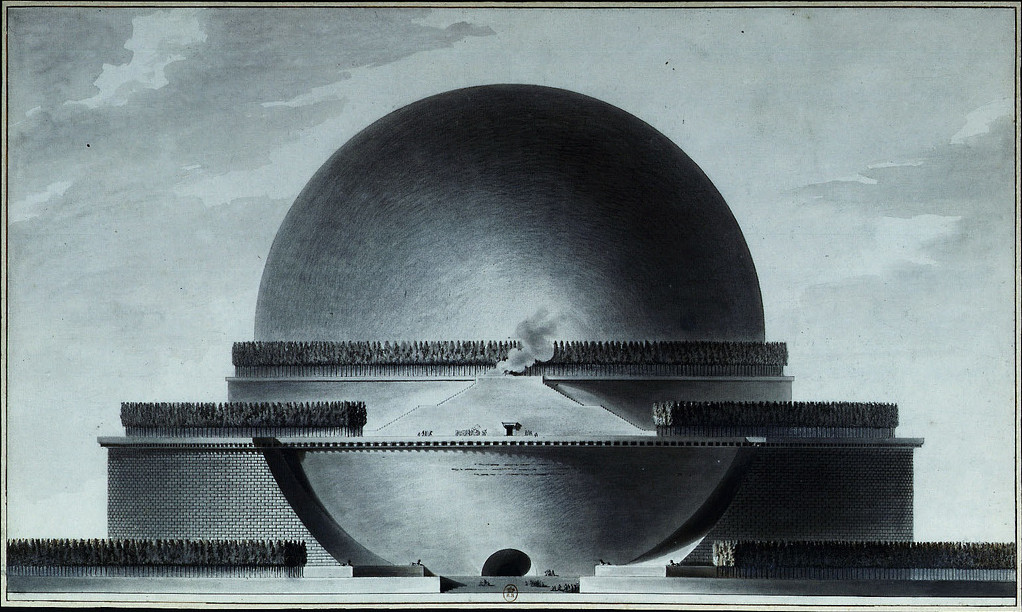

These included an updated colosseum, a spherical cenotaph for Isaac Newton taller than the Great Pyramids of Giza, a basilica meant to give its beholders an impression of the universe itself, a royal library of near-Borgesian proportions, and even an actual Tower of Babel.

For Boullée, bigger was better, an idea that would sweep global architecture a century and a half after his death. By the mid-twentieth century, the world had also come to accept a Boullée-like preference for minimal ornamentation as well as his conception of what his contemporaries jokingly termed architecture parlante: that is, buildings that “speak” about their purpose visually, and in no uncertain terms. (You can hear more about it in the video below, a segment by professor Erika Naginski from Harvard’s online course “The Architectual Imagination.”) When Boullée designed a Palace of Justice, he placed a courthouse directly over a jailhouse, articulating “one enormous metaphor for crime overwhelmed by the weight of justice.” This may have been a bit much even for the new French Republic, but for those who appreciated Boullée’s work, it pointed the way to the architecture of the future — a future we would later call modern.

via Aeon

Related content:

The World According to Le Corbusier: An Animated Introduction to the Most Modern of All Architects

The Unrealized Projects of Frank Lloyd Wright Get Brought to Life with 3D Digital Reconstructions

What Makes Paris Look Like Paris? A Creative Use of Google Street View

The Creation & Restoration of Notre-Dame Cathedral, Animated

Why Do People Hate Modern Architecture?: A Video Essay

How to Draw Like an Architect: An Introduction in Six Videos

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

0 Commentaires